By Manjeet Nanda

Whenever we think about the conveyor belt, we always visualise the moving baggage carousel at the airport. It moves the bags around in a circle.

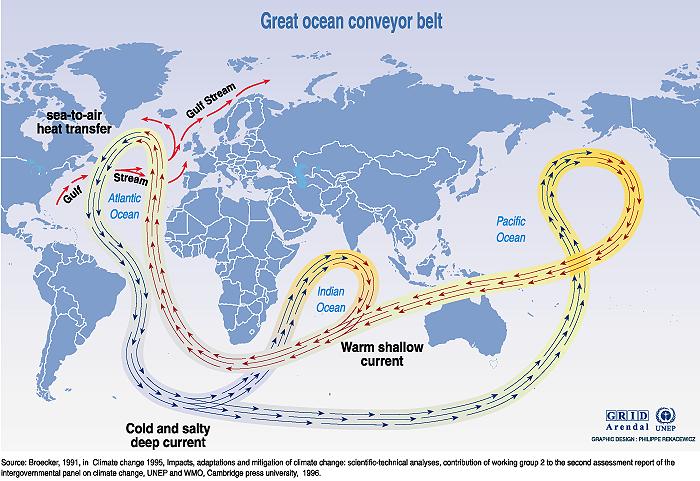

Today we are going to discuss a conveyor belt that transports water around the world. It is known as ‘The thermohaline circulation – the Global Conveyor Belt’. Sometimes it is also called ‘the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt’.

Before discussing the Global Conveyor Belt, let’s first understand the ocean currents. You know about ocean tides, but how much do you know about ocean currents?

Ocean currents are continuous movements of water in the ocean that follow set paths, kind of like rivers in the ocean. They can move water horizontally and vertically and occur on both local and global scales. They can be at the water’s surface or go to the deep sea 300 meters (984 feet). Surface currents make up about 10% of all the water in the ocean – the upper 400 meters of the ocean.

The ocean also has deep underwater currents. These are more massive but move more slowly than surface currents. Underwater currents mix the ocean’s waters on a global scale. They make up the other 90% of the ocean.

Currents are generally measured in meters per second or in knots (1 knot = 1.85 kilometers per hour or 1.15 miles per hour). Oceanic currents are driven by three main factors:

The rise and fall of the tides: Tides create a current in the oceans, which are strongest near the shore, and in bays and estuaries along the coast. These are called “tidal currents.” As the tide rises, the water moves, inland. This is called the flood current. As the tide recedes, the water moves seaward. This is called the ebb current. You can see the movement of water sitting on a beach. Tidal currents change in a very regular pattern and can be predicted for future dates. In some locations, strong tidal currents can travel at speeds of eight knots or more.

Wind: If we consider the surface of the ocean on a global scale over time, the surface currents are driven primarily by winds. Near coastal areas winds tend to drive currents on a localised scale and can result in phenomena like coastal upwelling. On a more global scale, in the open ocean, winds drive currents that circulate water for thousands of miles throughout the ocean basins.

You have probably heard of the famous current: the Gulf Stream. It transports nearly four billion cubic feet of water per second. Another one is Kurishio current, located off the east coast of Japan. This is oceans largest current. It can travel 25-75 miles a day and is equal in volume of 6000 large rivers. Surface ocean currents on the open ocean fantastically complicated and beautifully driven by complex global wind system.

Thermohaline circulation: After understanding the surface currents and their forces, it is time to understand the major force behind the deep underwater currents – Thermohaline circulation.

Thermohaline circulation moves a massive current of water around the globe, from northern oceans to southern oceans, and back again. Currents slowly turn over water in the entire ocean, from top to bottom. It is somewhat like a giant conveyor belt, moving warm surface waters downward and forcing cold, nutrient-rich waters upward.

The term thermohaline combines the words thermo (heat) and haline (salt), both factors that influence the density of seawater. The ocean is constantly shifting and moving in reaction to changes in water density. This belt affects the Earth’s climate by driving warm water from the equator and cold water from the poles around the Earth. It takes water almost 1000 years to move through the whole conveyor belt.